Thursday, December 6, 2012

Unforgettable Minn

By Brad Fisher

In 1951, Holling Clancy Holling muddied the waters of fiction and nonfiction and came up with a winner of a tall tale.

A snapping turtle, like the heroine of Holling Clancy Holling’s Minn of the Mississippi encountered in the wild, is a primeval, elemental thing. Even if she doesn’t bite you, she’s going to leave a mark. Her cragged, mossy back, long dinosaur tail and cruel predator’s jawline warn you that she is no dime-store pet. She is an ancient, alien intelligence that will take your arm — clean off — if she’s so inclined. Or, as in the fevered nightmare of a hapless human who meets Minn in her native element, she may just grab you by the belly and split you like a melon.

My own unforgettable encounter with Holling’s river monster took place at a suburban Seattle library in the summer of 1961. It wasn’t face to face, it wasn’t in the field, but it was memorable nonetheless.

Minn was ten years old at the time. I was nine, and was allowed, with a friend, to walk the half mile to the library. Our path cut across a hayfield and a blueberry farm, affording us irrigation ditches and filled-up tractor ruts that teemed with frogs and salamanders, which we often captured to bring home.

And perhaps it’s that casual, wet, green context that made Minn stick in the back of my mind for most of my life.

For Minn is nothing if not watery and green. The story of a snapping turtle who journeys the length of the Mississippi, Minn takes place under water much of the time. And so Holling’s lush, full-page watercolor illustrations run the spectrum from teal to emerald to rich gold and olive, fading into brown. His black-and-white margin illustrations of hatching turtle eggs and mighty watersheds are lush and wet even without color.

Minn was one of five well-known books that Holling wrote over a 15 year period that successfully combined natural history, geography, geopolitical history and and engaging fiction: Paddle to the Sea, The Tree in the Trail, Seabird and Pagoo. The best known books of his career, they won numerous awards and were touted in the elementary schools of the fifties and sixties. They’re all still in print, fueled by their popularity in home school curricula.

All of these wonderful books have in common a natural blend of fiction and nonfiction, art and narrative, reality and imagination. In Minn of the Mississippi, Holling found a way to create a current of history, geology, hydrology, geography, and nature that flowed with the main character on her life’s journey from Minnesota to New Orleans. To capture young imaginations, Holling used a legacy of nature writing by authors like Ernest Thomson Seton and others, who could personify, without anthropomorphizing, an animal like a grizzly bear or a snapping turtle. Holling maneuvers deftly from snapper to human perspective and back to suit his narrative and educational goals. His margin drawings compare the geographic shapes carved by the great river system to animals, people and objects in a way that forever changes the way you look at a map of the country. And his lush watercolors of everything from pirate treasure to pre-Columbian Indian mounds and riverine nightmares paint Minn’s world in vivid layers soaked in color. Caught in this enchanting stream, a nine-year-old boy would hardly know he was learning about the commerce and natural history of one of the world’s great watersheds.

Minn was the penultimate book in Holling’s series. It was not the most famous. That claim went to Paddle-to-the-Sea, which won a Caldecott Honor Book award, was made into a movie, and now claims its own amusement park in Canada. Minn, like its stolid, ungainly, under-the-surface heroine, left the limelight to others.

But you don’t want to underestimate the grip of an alligator snapping turtle. Minn hibernated under the surface of my childhood memories, staying buried until my own children reached the age of fascination with small creatures. We bought dozens of books to read to them, selecting from what was current at the time. Then one day, on a trip to the local library of our hometown in suburban Pittsburgh, Minn stirred in my imagination. This was the early nineties, so they still had a card catalog, and sure enough, the book was there. Perfect for a read to my young kids.

But not.

My eight-year-old son fell asleep. My five-year-old daughter wrinkled up her nose and demanded something different. Something with ponies. Not great.

I persisted for a few months, dragging out a paperbound copy that I’d bought. But at some point it became obvious that Holling’s lush art and equally vivid narrative would be lost on this generation, to judge by my kids, at least. My persistence became a family joke, an indication of how out of touch Dad was. And so I let Minn slip away.

Pity. Because, living in Pittsburgh, we might as well be in Minn’s back yard. After fifty years of our own peregrinations, my wife and I have spawned and raised our own brood of little snappers in the Ohio River watershed, in the heart of the great American network of Mississippi headwaters. (Coincidence? Perhaps.) The birthplace of environmentalist Rachel Carson, this is habitat for snappers like Minn, as well as great river catfish, muskellunge, steelhead, hellbenders and other primitive murky creatures ... different and perhaps more essentially American than the tree frogs and newts of my rain-washed childhood home in the Pacific Northwest. It’s also a combination of industrial and post-industrial watershed ... something Holling described without bias or romance in Minn of the Mississippi.

But times change. There are no hayfields or blueberry farms where we live, and water creatures are more likely to be something you encounter in a book than a mud puddle.

If you pick up the book, that is.

But there may be hope. I’ve been reading articles about the “Common Core” curriculum being proposed for public schools. There’s a fierce debate over how much fiction kids should read, and how much nonfiction — nonfiction being seen as important to the kind of analytical reading kids will have to do in the real world of desks and computers. I have no dog in that fight, although my daughter, who’s grown up and now preparing to be a high school English teacher, does. She’s the one who wrinkled up her nose at Minn and its gripping blend of fiction and nonfiction back in 1992.

Maybe I’ll get her to read it this time around.

Brad Fisher is a principal in the Pennsylvania public relations and advertising firm, B.R. Fisher. He’s a follower of this Holling blog, and we’re happy he offered us this charming memoir.

Tuesday, November 27, 2012

Holling for the Humanities in Schooling

All well and good if you want to catch the overnighter to Buffalo or bake a pie, but aren’t there more exciting, charming or inviting subjects? It’s easier to impart knowledge in a congenial, inviting manner than by force feeding children with turgid texts.

In researching the effect Holling has had I’ve been struck by the many recommendations for using his books for home schooling. Somewhat more than 2 percent of school-age children K-12 are home schooled. Their parents’ reasons are objections to school environment, desire for religious instruction and hopes for better education. Perhaps they also want to choose texts that are more enriching than this “Common Core.”

Beautiful Feet Books (at http://bfbooks.com/) believes that “the best children’s literature can both educate and inspire.” One of the popular products of this bookseller is its Geography Through Literature study guide and map set. It accompanies Holling’s Paddle-to-the-Sea, Tree in the Trail, Seabird and Minn of the Mississippi.

Literature is a significant part of home schooling. It’s obvious to even the casual reader that Holling’s story lines and splendid art and illustrations are guides that can introduce elementary students to a world of naturalism, the geography of America and the cultures that formed our country.

Another often-overlooked reason why Holling’s work succeeds in attracting children is its reading index. His Flesch Reading Index score is 75.2, meaning that 90% of other vocabulary is harder. Similarly, only 5% of Holling’s words are “complex. His vocabulary choices have just 1.4 syllables per word. (Difficult or foreign words are spelled phonetically.) And, there are an average of just 12.3 words per sentence.

Education fads swing into and out of favor, but currently there is great stress on the scientific and technical at the expense of the humanities. While we need mathematically adept professionals, it would be wonderful if there were an equal number of children who grow up making the liberal arts and literature a cornerstone of their lives.

Holling’s sidebar illustration from Tree in the Trail can’t help but capture a young student’s imagination.

The field of education is going through a massive reassessment, and students are being barraged with tests, studying for tests, and remedial reading to pass those tests. For good or ill, there’s a growing concentration on having students read non-fiction. Sara Moshe writes in this week’s New York Times that educators are foisting “historical documents, scientific tracts, maps, and other ‘informational texts’ like recipes and train schedules” onto beleaguered students.

All well and good if you want to catch the overnighter to Buffalo or bake a pie, but aren’t there more exciting, charming or inviting subjects? It’s easier to impart knowledge in a congenial, inviting manner than by force feeding children with turgid texts.

In researching the effect Holling has had I’ve been struck by the many recommendations for using his books for home schooling. Somewhat more than 2 percent of school-age children K-12 are home schooled. Their parents’ reasons are objections to school environment, desire for religious instruction and hopes for better education. Perhaps they also want to choose texts that are more enriching than this “Common Core.”

Beautiful Feet Books (at http://bfbooks.com/) believes that “the best children’s literature can both educate and inspire.” One of the popular products of this bookseller is its Geography Through Literature study guide and map set. It accompanies Holling’s Paddle-to-the-Sea, Tree in the Trail, Seabird and Minn of the Mississippi.

Home School Discount Products (at http://www.homeschooldiscountproducts.com/) also recommends four of those books plus Pagoo. Its employees are all home-schooled or are parents who home-school their children.

Literature is a significant part of home schooling. It’s obvious to even the casual reader that Holling’s story lines and splendid art and illustrations are guides that can introduce elementary students to a world of naturalism, the geography of America and the cultures that formed our country.

Another often-overlooked reason why Holling’s work succeeds in attracting children is its reading index. His Flesch Reading Index score is 75.2, meaning that 90% of other vocabulary is harder. Similarly, only 5% of Holling’s words are “complex. His vocabulary choices have just 1.4 syllables per word. (Difficult or foreign words are spelled phonetically.) And, there are an average of just 12.3 words per sentence.

Education fads swing into and out of favor, but currently there is great stress on the scientific and technical at the expense of the humanities. While we need mathematically adept professionals, it would be wonderful if there were an equal number of children who grow up making the liberal arts and literature a cornerstone of their lives.

Holling’s sidebar illustration from Tree in the Trail can’t help but capture a young student’s imagination.

Thursday, October 4, 2012

New Release Published

A new book has just been published that includes Holling Clancy Holling. Ink Trails, Michigan’s Famous and Forgotten Authors has been written by Dave and Jack Dempsey, brothers who are both established authors. Sixteen other authors are profiled.

Joan Hoffman mentioned this to me, and recalls, “I met Jack two years ago as he was looking for Holling Corners [where HCH was raised]. It is not a place you would easily find because that’s one of the local names long since discards.”

You can find the book at Amazon.com and other retailers ($14.41, available also for Kindle). Jack Lessenberry, senior political analyst at Michigan Radio, said, this is “a book that belongs on every Michigander’s shelf — after it has been devoured. I learned a great deal about several authors I’d long long admired…and more about fascinating people I have yet to discover.”

Thursday, September 20, 2012

Write What You Know: Holling Did

New writers are given basic advice to “write what you know.” This was key to Holling Clancy Holling’s career as a writer, illustrator and naturalist. He was first an inquisitive child growing up in rural Michigan and, second, one who learned skills at the hands of his family, relatives, co-workers and Native-American friends. The insights we gain by reading Minn of the Mississippi, Paddle-to-the-Sea and Seabird could only have come from a person who had hands-on knowledge of his environment and 19th century crafts, geography through personal exploration, and trial-and-error skills learned by canoeing and survival camping.

We’re fortunate that Hazel Gibb Hinman spent days interviewing Holling and his wife Lucille in 1957 for her Master’s thesis at the University of Redlands in California. She isolated Holling’s experiences and directly correlated them to his published work. For example, growing up in Michigan, Holling told Hinman, his father Bennett Clancy would point to a rock or boulder, asking, “Do you see the scratches on it? Do you suppose those scratches had anything to do with the glacial period?” Then, Papa Bennett would explain how the glaciers formed, packed the ice and snow, then pushed out and cut into the mountains. “How fast did the glaciers go?” Holling quoted his father. “Well, slowly,” showing with his hands the few inches the glaciers would travel in a year.

As Minn, a snapping turtle, grew to a two-year-old, Holling wrote [p.28, Minn of the Missippi, Houghton Mifflin Company], “Glaciers had spread clay, gravel, and big stones across this northland. Minn found rivers running on boulder beds. She might dig in clay, sand or muck. But she found boulders beneath her. She entered cuts in solid granite and sea-laid stone, ground out by swirling water with gravel and sand.” Papa Bennett’s lessons had been well learned.

Holling worked on board the large ships plying the Great Lakes. Over the years he also became an experienced canoer and wilderness trekker. His familiarity with waterways large and small got him through many scrapes, and they supported his writing in Minn of the Mississippi, Pagoo and Paddle-to-the-Sea. He writes in Minn [p.34], “The next spring she found the River raging. It could cut down bluffs and rebuild them again as islands. Some islands held trees scarred by ice and logs heaved out at them by floods. Floods left trees with their trunks clay-coated ten feet up; drying in neat, level lines of whitewash. Floods left brush in ghostly branches like nests of giant birds.”

Traveling cross-country by trailer in 1937, Holling and his wife Lucille told Hinman, they stopped by the Ohio Mound Builders. Information and sketches concerning the remains, Hinman states, was worked into Minn’s adventures as well [p. 46]. “The ancient Mound Builders, gone for centuries, might not be real to Minn — but now they caused her no end of trouble. In hastily digging out her nest…she kicked up obsidian arrowheads, bits of clay pottery, a carved-stone pipe…. For such treasures any museum director might have given Minn a private pool, fresh meat for a lifetime, unlimited rest and quiet.”

Camping in at Landa Park between Austin and San Antonio allowed Holling to explore New Braunfels, including a section of the Mississippi, a huge spring and a lake. This, too, was added to Minn’s expedition as she neared the end of her journey. A visit to friends in Houma, La., also had afforded the Hollings a guided tour through the bayous.

In 1926, a year after Holling and Lucille Webster were married, they served on an around-the world cruise as artists, teaching passengers as they sailed through the Caribbean en route to Asia. In Panama City, he sketched and explored, writing in the shipboard publication about an underwater treasure chest spilling its contents. This image showed up, writing in 1951, as Minn lived “on a glittering heap — of what? Rich jewels, once more, were merely stones; and one of earth’s heaviest elements — melted neatly into golden wafers of equal weight — was returned once again to the care of earth and water. For Minn, her doorstep of so-called treasure was only a hardness, like water-worn pebbles.” [p. 84]

How does a writer experience an underwater world in the late 1930s before snorkel tubes and scuba tanks? Holling, Hinman, reports, secured some goggles and five feet of garden hose to do his explorations. This was Holling’s “fish-eye view” that he translated into Minn’s world.

Holling was acquisitive in his knowledge and adept at working it later into story line and marginal illustrations. It might be said that Holling’s books reflect a lifetime of learning that has been shared by generations of young readers.

Thursday, August 9, 2012

Holling in Hollywood: The Missing Art

Much of Holling’s work for Disney is uncredited. Worse, virtually none of it was released to the public. An animated feature of Hiawatha was to be based on Longfellow’s 1855 poem. The 1937 film Little Hiawatha was kept in development for many years, and Holling would have contributed rough sketches. They’re mindful of the early Disney work audiences can still see in films like Pinocchio. Sadly, the picture has never been made.

We do know that a trip Holling and others from the studio made to Mexico, Guatemala and El Salvador Oct. 8 to 30, 1943, influenced him greatly. Holling’s formal report noted a hurricane in Mazatlan had rolled their plane into a building where a wing was torn off. Afterwards, he writes, “We come to sunny Mexico where the beauties of Architecture, the simple dignity of the People and the lush coloring of Nature combine to give a group of artists and writers…quite a dither to decide whether to start sketching like mad or writing like mad.”

With tongue in cheek, he then declaims on the tortilla, which “hasn’t the felt-inner-sole feel of a griddle cake, but rather of some strange new plastic…. And thus we come to the taco.” He continues, “The trick is to eat salad and plate together and come out even.”

Holling made many sketches of the people and places the group visited, of which at least 21 are preserved in the UCLA archives. (Many more sketches centered on World War II images, his own studies, and scenes he saw of everyday Latinos and a medical clinic.) But, what strikes one as the perfect combination of Holling’s exposure to Mexico and the Disney experience are his two charming illustrations of the Corn People. The animation of corn kernels marching off the cob marries the naturalistic environment he was so fond of with a wry sense of humor.

It’s amazing to wonder what would have come from Holling’s paint brushes and typewriter if he had continued at the Disney studio. But, then, we might not have had the succession of books published by Houghton Mifflin.

Saturday, July 28, 2012

Holling in Hollywood: Who Knew?

Few people realize there was a period when Holling Clancy Holling worked at the iconic Walt Disney Company. Holling and Lucille had moved west from Chicago to Altadena, Cal., in 1938, and subsequently to Pasadena. He had published Tree in the Trail for Houghton Mifflin in 1942, but Seabird wouldn’t appear until 1948. Disney had released Dumbo in 1941 and Bambi in 1942. Like any journeyman illustrator, Holling needed work.

The leading film animation enterprise in the area at that time was Walt Disney’s new studio in Burbank. Hazel Gibb Hinman wrote in her thesis in 1958 that Holling was hired and worked as “crew” there from 1942 to ’47. Other research indicates he was employed there on a project basis or full-time from 1943 to ’44, and again for a short period in 1955.

Regardless of the precise dates, Holling’s work in the film industry is now coming to light. He was proud that he was given recognition when the “Rite of Spring” portion of Fantasia was to be re-released as A World Is Born for school students. Holling was tasked with writing the narrative to accompany Igor Stravinsky’s ballet. The UCLA Library has archived these portions of four drafts for a “credit title.” Holling’s final draft begins….

“Our planet has printed its past on tablets of buried rock. Modern science can translate these record of earth-writing.

“This picture, in general, follows scientific findings. It shows happenings millions of years before man existed. The story is told with color, movement, music, words—with rhythm and some degree of poetic license.”

The 16 mm film portrayed whimsical animation of one-celled organisms, fish climbing out of the sea, creatures devouring each other as a symbol of Darwinian evolution, and the ancient creatures’ eventual march to extinction

Holling wrote to his sister in April 1944 describing his work on this film. Joan Hoffman writes, “Then on the 8th page he hand wrote on the side ‘P.S. 5 p.m. First reading to the big shots went well — will read for Walt next week.’”

The film was to be projected, Holling would read his script as the film rolled, and Stravinsky’s music would be played, Hazel Hinman Gibb wrote in her Master’s thesis. Mr. Disney and his brother Roy were expectant. With the sound mixer standing by, the executives wanted to judge the script and a rough cut. In horror, however, they realized someone had forgotten to bring the film to the screening!

Walt was getting restless and ordered Holling to begin the narration. As soon as Holling started reading the prose poem he had written, Walt relaxed. When he was finished, Walt said “I don’t think we need to look any further for a voice. Let Holling do it.” The film was finally released in 1955.

A Presumptuous Request Holling wrote to Mr. Disney in 1933 at “Mickey Mouse Studios, Hollywood” asking for work. He presented his credentials: “I am not a poor artist in search of a job. I do various things, such as writing and illustrating children’s’ books (there are eight on the market), advertising illustrations, designing of everything from trade marks to dude ranches.”

He continued presumptuously, “I can draw, I know what I draw and why, I know color, and I know what the public wants.” For whatever reason, Holling never mailed the letter, which now resides in the UCLA archives.

Note: In preparing these thoughts, I’m indebted to the efforts of Didier Ghez, blogger and researcher, and to Joan Hoffman, curator of the Holling Collection at the Leslie Area Historical Museum.

The leading film animation enterprise in the area at that time was Walt Disney’s new studio in Burbank. Hazel Gibb Hinman wrote in her thesis in 1958 that Holling was hired and worked as “crew” there from 1942 to ’47. Other research indicates he was employed there on a project basis or full-time from 1943 to ’44, and again for a short period in 1955.

Regardless of the precise dates, Holling’s work in the film industry is now coming to light. He was proud that he was given recognition when the “Rite of Spring” portion of Fantasia was to be re-released as A World Is Born for school students. Holling was tasked with writing the narrative to accompany Igor Stravinsky’s ballet. The UCLA Library has archived these portions of four drafts for a “credit title.” Holling’s final draft begins….

“Our planet has printed its past on tablets of buried rock. Modern science can translate these record of earth-writing.

“This picture, in general, follows scientific findings. It shows happenings millions of years before man existed. The story is told with color, movement, music, words—with rhythm and some degree of poetic license.”

The 16 mm film portrayed whimsical animation of one-celled organisms, fish climbing out of the sea, creatures devouring each other as a symbol of Darwinian evolution, and the ancient creatures’ eventual march to extinction

Holling wrote to his sister in April 1944 describing his work on this film. Joan Hoffman writes, “Then on the 8th page he hand wrote on the side ‘P.S. 5 p.m. First reading to the big shots went well — will read for Walt next week.’”

The film was to be projected, Holling would read his script as the film rolled, and Stravinsky’s music would be played, Hazel Hinman Gibb wrote in her Master’s thesis. Mr. Disney and his brother Roy were expectant. With the sound mixer standing by, the executives wanted to judge the script and a rough cut. In horror, however, they realized someone had forgotten to bring the film to the screening!

Walt was getting restless and ordered Holling to begin the narration. As soon as Holling started reading the prose poem he had written, Walt relaxed. When he was finished, Walt said “I don’t think we need to look any further for a voice. Let Holling do it.” The film was finally released in 1955.

A Presumptuous Request Holling wrote to Mr. Disney in 1933 at “Mickey Mouse Studios, Hollywood” asking for work. He presented his credentials: “I am not a poor artist in search of a job. I do various things, such as writing and illustrating children’s’ books (there are eight on the market), advertising illustrations, designing of everything from trade marks to dude ranches.”

He continued presumptuously, “I can draw, I know what I draw and why, I know color, and I know what the public wants.” For whatever reason, Holling never mailed the letter, which now resides in the UCLA archives.

Note: In preparing these thoughts, I’m indebted to the efforts of Didier Ghez, blogger and researcher, and to Joan Hoffman, curator of the Holling Collection at the Leslie Area Historical Museum.

Saturday, July 7, 2012

It Was the Tautonym* that Enchanted Me

Strange things capture a young boy’s attention, and for me it was the curiosity of an author having the same given name as his surname. Holling Clancy Holling has the strange beauty of a harsh Irish name bookended by two action words, or gerunds.

It wasn’t always so. HCH was born Holling Allison Clancy in the eponymous Holling Corners, Mich. His forebears had lived and farmed there for generations. He legally changed his name in 1925, the same year that he married Lucille Webster. Holling was his mother’s maiden name, according to Joan Hoffman, who curates the Leslie Area Historical Museum.

“While attending the Art Institute of Chicago,” she writes, “he used Holling as his signature and became known as Mr. Holling, except by those who knew him well. Another contributing factor [to the name change] was that there were ample Clancy cousins to carry on the name — his father was one of 12 children — unlike the surname Holling that had come to an end.” Only once prior to 1925 did he use that signature as a pen name.

If a writer wants to keep his or her name on readers’ lips, there are worse ways than to name yourself redundantly. There is the British writer Jerome K. Jerome (1859-1927), whose father was responsible for the surname change. And Ford Madox Ford (1873-1939), who changed his name in 1919 because “Hueffer” may have sounded too German.

William Cole whimsically outlined the situation in “Mutual Problem:”

Said Jerome K. Jerome to Ford Madox Ford,

‘There's something, old boy, that I've always abhorred:

When people address me and call me, ‘Jerome’,

Are they being standoffish, or too much at home?’’

Said Ford, ‘I agree; it's the same thing with me.’

* A tautonym is a scientific name in which the same word is used for genus and species. For example, the red fox is Vulpes vulpes and the black rat is Rattus rattus. Thus, Holling Clancy Holling is both genus and species for author and artist and naturalist. Makes sense, no?

It wasn’t always so. HCH was born Holling Allison Clancy in the eponymous Holling Corners, Mich. His forebears had lived and farmed there for generations. He legally changed his name in 1925, the same year that he married Lucille Webster. Holling was his mother’s maiden name, according to Joan Hoffman, who curates the Leslie Area Historical Museum.

“While attending the Art Institute of Chicago,” she writes, “he used Holling as his signature and became known as Mr. Holling, except by those who knew him well. Another contributing factor [to the name change] was that there were ample Clancy cousins to carry on the name — his father was one of 12 children — unlike the surname Holling that had come to an end.” Only once prior to 1925 did he use that signature as a pen name.

If a writer wants to keep his or her name on readers’ lips, there are worse ways than to name yourself redundantly. There is the British writer Jerome K. Jerome (1859-1927), whose father was responsible for the surname change. And Ford Madox Ford (1873-1939), who changed his name in 1919 because “Hueffer” may have sounded too German.

William Cole whimsically outlined the situation in “Mutual Problem:”

Said Jerome K. Jerome to Ford Madox Ford,

‘There's something, old boy, that I've always abhorred:

When people address me and call me, ‘Jerome’,

Are they being standoffish, or too much at home?’’

Said Ford, ‘I agree; it's the same thing with me.’

* A tautonym is a scientific name in which the same word is used for genus and species. For example, the red fox is Vulpes vulpes and the black rat is Rattus rattus. Thus, Holling Clancy Holling is both genus and species for author and artist and naturalist. Makes sense, no?

Monday, May 21, 2012

Tree in the Trail, the Newest Septuagenarian

Tree in the Trail will be 70 years old this year — not a long time in some trees’ lives, but an eternity for many books. Still, readership of this evergreen classic (no pun) continues to grow. Parents are still buying the book for their children, as are grandparents who want to share a country whose values are changing too quickly.

Tree in the Trail will be 70 years old this year — not a long time in some trees’ lives, but an eternity for many books. Still, readership of this evergreen classic (no pun) continues to grow. Parents are still buying the book for their children, as are grandparents who want to share a country whose values are changing too quickly.

Holling tells the story of a young Native-American boy in New Mexico who nurtures and protects a cottonwood sapling from bison who water nearby. Years later, in the 1540s, Coronado passes by the tree in his search for gold, the Sioux journey through the area, and the Spanish camp out beneath its branches. They’re followed by trappers and pioneers who trek across what becomes the Santa Fe Trail. Three hundred years pass before the tree grows old and dies, but its wood is fashioned into an ox yoke by Jed Simpson, a wagon-master. This lends a kind of immortality to the tree.

Half of the beauty in this book lies in the paintings and illustrations by Holling and his wife Lucille. The sidebar drawings are particularly choice (and instructive) as Holling shows how wood was cut and shaped into a yoke, draws diagrams of a Conestoga wagon, provides area maps, and explains types of arrowheads. It’s no wonder that home-schooling parents keep coming back to Holling’s work to teach natural history.

In fact, it’s time for me to order a copy for my five-year-old grandson. My copy of Tree in the Trail was bought by my parents for my brother in June 1944. The cover is torn, the binding is wobbly, and it smells like an old book, but I love it. Happily, copies are still available for less than $10.00. Isn’t that remarkable in this day and age of texting, speed reading and disposable writing?

A Surprise Discovery I was looking at online bookstores to see how readers have received the book, and discovered a review from 1999. Nedd Mockler wrote on the Amazon.com Web site, “Fifty-seven years ago at the request of his mother I visited Holling C. Holling at his California ranch. I was eight years old. He asked me to pose for a few sketches he wanted to do. Later that year he sent me the book Tree in the Trail. Inside the front cover he had written ‘For Nedd Mockler, who posed for the Indian boy in this book. With best wishes, Holling C. Holling.’ The inscription is dated Dec. 1942.”

I’ve written to Mr. Mockler asking for other reminiscences he has of this exciting event and will share any results with you.

Monday, April 23, 2012

Behind Every Successful Man…

While there’s an increasing volume of information concerning Holling Clancy Holling, there is much less biographical data on Lucille Webster, his wife. Yet, Lucille was an artist and professional in every way — and some of Holling’s success must be accorded to her.

Lucille Webster was born on Dec. 8, 1900, in Valparaiso, Ind. In Chicago, she designed theatrical scenery and costumes, and drew for fashion publications. A mutual friend introduced Holling to Lucille and her older sister who shared an art studio in the city. She remembers going out with Holling on a nice first date at a Chinese restaurant, but it wasn’t until she attended the Art Institute the following year that Holling was re-introduced to her during one of the open houses the girls had. That night, Holling and Lucille planned a world tour and began seeing each other steadily.

While Holling grew up in rural Michigan in a large family of devoted Methodists, Lucille was in some ways his opposite. She was a city girl whose father and a baby brother died early. There was no apparent religious observance. She had one sister, also an artist but reportedly unstable.

Still, they were married in 1925. The following year, the couple went on the first University World Cruise, where she designed for the drama department.

She and Holling became a couple in every sense of the word, as together they produced national advertising art and foreign travel brochures. Lucille illustrated a number of books for other authors, including Kimo, the Whistling Boy by Alice Cooper Bailey (1928); Songs from around a Toadstool Table by Rowena Bastin Bennett (1930); and the cover of Oriental Stories, a pulp magazine (1931). Together with Holling, she also illustrated textbooks. Among the Hollings' joint publications are Choo-Me-Shoo (1928), The Book of Indians (1935) and The Book of Cowboys (1936).

Joan Hoffman notes that Lucille made a specific contributions to two Houghton Mifflin books. “In Pagoo, all those microscopic drawings are hers and her name appears along with Holling's as illustrator on the title page. In the acknowledgment for Tree in the Trail, Holling gives Lucille credit for helping to complete the illustrations, research on trail data and for designing the colored map at the end.” Holling confessed, Joan says, “that Lucille draws women and children better than I do.”

While Holling had come from an extended family, Lucille seemed to have less family involvement. This may have been a reason Lucille wanted to settle down and have a home before Holling did. Moving to California, she worked with her husband on books. In 1951, she designed and oversaw the construction of their studio residence — their first home — in Pasadena. She died on 31 December 1989. Sadly, the Hollings had no children.

Wednesday, April 18, 2012

Keeping a Legend Alive in Michigan

Before going further into some developments taking place regarding Holling’s career, I want to stop and credit the work being done in Leslie, Mich. Holling’s home town is also the home of the Leslie Area Historical Museum and a special area devoted to Holling's art, writing and achievements.

Joan Hoffman, who curates the Holling collection, describes activities there. “The Leslie Area Historical Museum operates under the charter, constitution and by-laws of the Leslie Area Historical Society. The museum workers are custodians of the many historical items, which are cataloged, displayed and properly cared for. The City of Leslie has provided the space we use."

Joan Hoffman

“The Society's function is more fund-raising and lining up public historical programs. They played a big part in the recent 175th anniversary of Leslie. It was Steve Hainstock's vision and effort that initiated both the Society and Museum in 2007. He has a wealth of historical knowledge, and we look to him often for guidance.

“Leslie is a small town,” Joan says. “A major highway once went through town. Since Route 127 was moved to the west and hooked up with the Interstate highway system, many businesses that once were in Leslie are now gone. It seems to me Leslie is looking for its identity like many towns where the major road now bypasses them. Leslie and the area have a lot of history, and that is what a few of us are trying to promote.”

One function of the museum is to be there for visitors, serving individuals and groups. “Groups like Scouts come yearly. We have school groups sometimes and the Chamber of Commerce once a year. One of our people is particularly good at genealogy and maintains a file on families. We work with the town library and have had small displays in their display case, and for awhile we had displays in a vacant store front.”

The Historical Society and Holling collection is housed in the G.A.R. (Grand Army of the Republic) building represented in this postcard. This is on Bellevue, a short distance east of Main St.

“Above the upper window arch,” Joan points out, “are 13 upright rectangular stones that follow that curve. Those represent the thirteen original states. The pole that looks like it divides the window and the 13 stones is a flagpole.

There are only two floors, none at ground level. The museum is in a room in the basement. “See what looks like grates to the left of the steps?” she asks. “Those are our basement museum windows. The corner stone just to the left of the basement windows says 1903.”

If you’re traveling through southern Michigan, you’re invited to take a little time to visit the Holling collection and learn more about one of America’s favorite writers. The Leslie Area Historical Museum is at 107 E. Bellevue Rd., P.O. Box 275, Leslie, MI 49251; 517-589-5220.

Joan Hoffman, who curates the Holling collection, describes activities there. “The Leslie Area Historical Museum operates under the charter, constitution and by-laws of the Leslie Area Historical Society. The museum workers are custodians of the many historical items, which are cataloged, displayed and properly cared for. The City of Leslie has provided the space we use."

Joan Hoffman

“The Society's function is more fund-raising and lining up public historical programs. They played a big part in the recent 175th anniversary of Leslie. It was Steve Hainstock's vision and effort that initiated both the Society and Museum in 2007. He has a wealth of historical knowledge, and we look to him often for guidance.

“Leslie is a small town,” Joan says. “A major highway once went through town. Since Route 127 was moved to the west and hooked up with the Interstate highway system, many businesses that once were in Leslie are now gone. It seems to me Leslie is looking for its identity like many towns where the major road now bypasses them. Leslie and the area have a lot of history, and that is what a few of us are trying to promote.”

One function of the museum is to be there for visitors, serving individuals and groups. “Groups like Scouts come yearly. We have school groups sometimes and the Chamber of Commerce once a year. One of our people is particularly good at genealogy and maintains a file on families. We work with the town library and have had small displays in their display case, and for awhile we had displays in a vacant store front.”

The Historical Society and Holling collection is housed in the G.A.R. (Grand Army of the Republic) building represented in this postcard. This is on Bellevue, a short distance east of Main St.

“Above the upper window arch,” Joan points out, “are 13 upright rectangular stones that follow that curve. Those represent the thirteen original states. The pole that looks like it divides the window and the 13 stones is a flagpole.

There are only two floors, none at ground level. The museum is in a room in the basement. “See what looks like grates to the left of the steps?” she asks. “Those are our basement museum windows. The corner stone just to the left of the basement windows says 1903.”

If you’re traveling through southern Michigan, you’re invited to take a little time to visit the Holling collection and learn more about one of America’s favorite writers. The Leslie Area Historical Museum is at 107 E. Bellevue Rd., P.O. Box 275, Leslie, MI 49251; 517-589-5220.

Saturday, March 24, 2012

Pictures and Verse from the Past: Follow-up

It is, of course, a major discovery to find a previously unknown daVinci mural hidden behind a painting done years afterwards. But to bibliophiles who cherish Holling’s writing, painting and craftsmanship, it’s equally thrilling to find another copy of a long-lost book after 89 years.

Heather Heath in Livingston, Mont., found Sun and Smoke among donated books, then tracked down the Leslie Area Museum. (Photo by AP)

Heather Heath found Sun and Smoke: a Book of New Mexico Verse among donations to the Community Closet thrift shop in Livingston, Mont. She was the detective who set it aside for further examination, knowing there was something special about the limited edition work. She learned from the online auction site, eBay, that an estimated the value might be $235. This news began making the area papers. Associated Press writer Liz Kearney, chronicling the discovery, notes that Heath wondered at the inscription in the book: “To Florence and Dan, in memory of the 711 Ranch.” Who were Florence and Dan, had Holling ever visited Montana, and where was the 711 Ranch?

Heath then searched the Internet for information about Holling. (She may even have visited this blog.) From biographical information about Holling’s birthplace, she then tracked down Steve Hainstock, a past president and co-founder of the Leslie Area Museum in Michigan. He told her Sun and Smoke was the only book which the museum did not have. Heath stated in the AP story, “It was exciting to get this gentleman on the phone and hear him say ‘Wow!’”

In the spirit of the Community Closet’s policy of sharing with other nonprofits, Executive Director Caron Cooper secured permission to donate the book to the Leslie Area Museum. The folks in Leslie are eagerly awaiting an opportunity to see the verses and art Holling created over three-quarters of a century ago.

A story like this might have remained localized in Livingston, Mont., and Leslie, Mich. Happily, we live in a digital age, when search engines bring the world to our fingertips, communication links span vast distances, and the past is easily accessed by interested audiences everywhere. With so much sad news and tension in the world, it’s satisfying to know a writer like Holling Clancy Holling is still extolling the panorama that is America. And that one more view — of New Mexico in verse and art — has come to light.

Note: Sun and Smoke arrived in Leslie Friday, Mar. 23. Joan Hoffman said, “I went over to the Hainstocks’ house and saw it as the box was opened. The spine of the book is not good, so the book is in quite fragile condition. Steve plans to scan the pages so it won’t have to be handled further.”

Heather Heath in Livingston, Mont., found Sun and Smoke among donated books, then tracked down the Leslie Area Museum. (Photo by AP)

Heather Heath found Sun and Smoke: a Book of New Mexico Verse among donations to the Community Closet thrift shop in Livingston, Mont. She was the detective who set it aside for further examination, knowing there was something special about the limited edition work. She learned from the online auction site, eBay, that an estimated the value might be $235. This news began making the area papers. Associated Press writer Liz Kearney, chronicling the discovery, notes that Heath wondered at the inscription in the book: “To Florence and Dan, in memory of the 711 Ranch.” Who were Florence and Dan, had Holling ever visited Montana, and where was the 711 Ranch?

Heath then searched the Internet for information about Holling. (She may even have visited this blog.) From biographical information about Holling’s birthplace, she then tracked down Steve Hainstock, a past president and co-founder of the Leslie Area Museum in Michigan. He told her Sun and Smoke was the only book which the museum did not have. Heath stated in the AP story, “It was exciting to get this gentleman on the phone and hear him say ‘Wow!’”

In the spirit of the Community Closet’s policy of sharing with other nonprofits, Executive Director Caron Cooper secured permission to donate the book to the Leslie Area Museum. The folks in Leslie are eagerly awaiting an opportunity to see the verses and art Holling created over three-quarters of a century ago.

A story like this might have remained localized in Livingston, Mont., and Leslie, Mich. Happily, we live in a digital age, when search engines bring the world to our fingertips, communication links span vast distances, and the past is easily accessed by interested audiences everywhere. With so much sad news and tension in the world, it’s satisfying to know a writer like Holling Clancy Holling is still extolling the panorama that is America. And that one more view — of New Mexico in verse and art — has come to light.

Note: Sun and Smoke arrived in Leslie Friday, Mar. 23. Joan Hoffman said, “I went over to the Hainstocks’ house and saw it as the box was opened. The spine of the book is not good, so the book is in quite fragile condition. Steve plans to scan the pages so it won’t have to be handled further.”

Monday, March 12, 2012

Breaking News: Pictures and Verse from the Past

A copy of Sun and Smoke: A Book of New Mexico has appeared! This is momentous news, as only 50 copies of Holling’s handmade book were published in 1923. Four copies are in university libraries and a fifth was sold last year by a rare books dealer.

On Feb. 8, Joan Hoffman learned that “a woman in Montana found a copy of Holling’s rare book in the thrift shop where she works.” A month later, Joan received a call and discovered “they’re donating the book to the Leslie Historical Museum. We were not sure we would get it, and certainly didn’t expect it to be an outright gift.” The book's delivery will be delayed at least until the local press is able to cover the story.

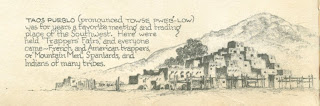

Sun and Smoke was created as a printing arts project when Holling was at the Art Institute of Chicago. The subject matter drew on the preceding months Holling had been in New Mexico. He had traveled extensively by horseback, took in the Taos art scene (and began appreciating color in his own painting), and worked at the ranch where he and Lucille Webster Holling were staying. He wrote the verses, carved wood blocks out of maple to illustrate and decorate the poems, and printed the 36-page book on hand-laid Fabriano paper from Italy. Both the printing and binding — culminating in a 6-1/2 by 10-1/4-inch book — were performed by Holling himself. This was truly an epic example of Holling’s craftsmanship.

Joan comments, “ I know Holling wanted to preserve his impressions of time spent in New Mexico, which he did in Sun and Smoke. I am anxious to see the poems and illustrations he used.”

We all are.

Labels:

Holling Clancy Holling,

rare books,

Sun and Smoke

Friday, March 2, 2012

No One Gets Mad Because the Writing Is Too Simple

In the introduction to Dr. Seuss’s The Bippolo Seed and Other Lost Stories, scholar Charles D. Cohen mentions a three-year-old who recited an entire Seuss story! The epiphany for author Theodor Geisel was that children absorb amazing volumes of information through their ears — lesser amounts through their eyes.

Key to Holling’s success was a Fog reading index of 6.9 — meaning that 91 percent of everyday words we use are more difficult. Only 5 percent of Holling’s words are foreign or complex. His choices average just 1.4 syllables per word. And, there are just 12.3 words per sentence.

It’s sometimes difficult to slide past polysyllabic environmental terms, or words in other languages. But Holling helps us in those instances, too. Tree in the Trail contains an amazing wealth of sidebar illustrations that explain history or define place names. In describing Coronado’s search for gold [chap. 5; unpaginated], he mentions an Indian town, Zuñi. The pronunciation — zoon-yee — is added parenthetically. Likewise, Santa Fe is spelled phonetically. Describing a Southwest trading and meeting place [chap. 9} he gives us Taos Pueblo and clarifies it as towse pweb-lo. This ease-of-entry is a secret to Holling’s enduring interest among young people and the home-schooled. Dr. Seuss, I think, would agree.

(A note of thanks for to E.J. Hirsch, Jr. for What Your Fifth Grader Needs to Know: Fundamentals of a Good Fifth Grade Education, from which these statistics are cited.)

Thursday, February 2, 2012

Forget Winter and Gaze at Lake Nipigon

A great part of our country is locked in cold and often-gray weather. We spend the winter months dreaming of spring, the return of migrating birds, and memories of swimming in warm waters. But remember: Paddle-to-the-Sea was born on a snowy hillside in Ontario.

If it will help you visualize Paddle’s home, take a moment to look at Lake Nipigon (from the Ontario Parks Dept.) and think of the adventurous route Paddle-to-the-Sea took.

This comes alive again in Deborah Cramer’s commentary that “we are connected to the ocean even if we can’t see it.” She writes (at http://seaaroundyou.com/paddle-to-the-sea/), “In this beloved children’s book, first published in 1941 but still in print, an Indian boy living in the Canadian wilderness near Lake Nipigon carves a canoe and a paddler. When he hears the cry of wild geese returning at the end of winter, he places Paddle-to-the-Sea on a snowy hill behind his home, facing south.”

Ms. Cramer is the author of Great Waters: An Atlantic Passage. Her description of Paddle’s route takes us again through Lake Superior and into Lakes Michigan, Huron, Erie and Ontario, dropping hundreds of feet through rough waters and calm eddies. Holling symbolically illustrated this wealth of clean water in his sidebar comparing the Great Lakes to cups pouring into each other.

She warns, however, that the “watery lifeline” between Paddle-to-the-Sea’s Nipigon River and the ocean are in danger. “If the earth continues to warm, water levels in the Great Lakes will drop. Tiny Paddle-to-the-Sea might make the long journey, but the shallower water may inhibit large cargo ships that ply the waters of the Great Lakes today.”

You can choose whether Holling was first an illustrator, a magnificent storyteller or a naturalist. It's practically impossible to put priorities on a man who so artfully wove the three disciplines together. Paddle-to-the-Sea is as indelibly wedded to the Great Lakes, St. Lawrence Seaway and Atlantic Ocean as Minn was to the Mississippi, Tree in the Trail to the Great Plains, and Seabird to life in the north Atlantic. This is our heritage as much as it is the legacy of these timeless stories.

Deborah Cramer is the author of Smithsonian Ocean: Our Water Our World, the companion to the new Sant Ocean Hall at the National Museum of Natural History. She lives by the edge of the sea, is a visiting scholar at the Earth Systems Initiative at MIT, and speaks frequently to educators and the public about the meaning of the sea in our lives. More information about her and her work can be found at http://deborahcramer.com/

If it will help you visualize Paddle’s home, take a moment to look at Lake Nipigon (from the Ontario Parks Dept.) and think of the adventurous route Paddle-to-the-Sea took.

This comes alive again in Deborah Cramer’s commentary that “we are connected to the ocean even if we can’t see it.” She writes (at http://seaaroundyou.com/paddle-to-the-sea/), “In this beloved children’s book, first published in 1941 but still in print, an Indian boy living in the Canadian wilderness near Lake Nipigon carves a canoe and a paddler. When he hears the cry of wild geese returning at the end of winter, he places Paddle-to-the-Sea on a snowy hill behind his home, facing south.”

Ms. Cramer is the author of Great Waters: An Atlantic Passage. Her description of Paddle’s route takes us again through Lake Superior and into Lakes Michigan, Huron, Erie and Ontario, dropping hundreds of feet through rough waters and calm eddies. Holling symbolically illustrated this wealth of clean water in his sidebar comparing the Great Lakes to cups pouring into each other.

She warns, however, that the “watery lifeline” between Paddle-to-the-Sea’s Nipigon River and the ocean are in danger. “If the earth continues to warm, water levels in the Great Lakes will drop. Tiny Paddle-to-the-Sea might make the long journey, but the shallower water may inhibit large cargo ships that ply the waters of the Great Lakes today.”

You can choose whether Holling was first an illustrator, a magnificent storyteller or a naturalist. It's practically impossible to put priorities on a man who so artfully wove the three disciplines together. Paddle-to-the-Sea is as indelibly wedded to the Great Lakes, St. Lawrence Seaway and Atlantic Ocean as Minn was to the Mississippi, Tree in the Trail to the Great Plains, and Seabird to life in the north Atlantic. This is our heritage as much as it is the legacy of these timeless stories.

Deborah Cramer is the author of Smithsonian Ocean: Our Water Our World, the companion to the new Sant Ocean Hall at the National Museum of Natural History. She lives by the edge of the sea, is a visiting scholar at the Earth Systems Initiative at MIT, and speaks frequently to educators and the public about the meaning of the sea in our lives. More information about her and her work can be found at http://deborahcramer.com/

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)