A note from Joan Hoffman at the museum in Lisle, Mich., intrigued me regarding Watty Piper and the publisher, Platt & Munk. Who was this prolific writer and where did Holling Clancy Holling fit into the publishing scheme?

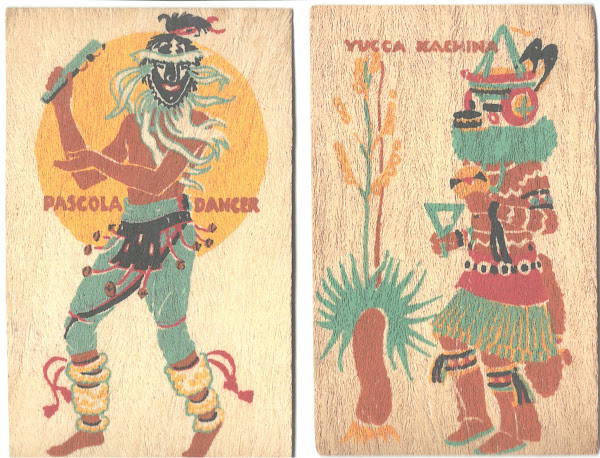

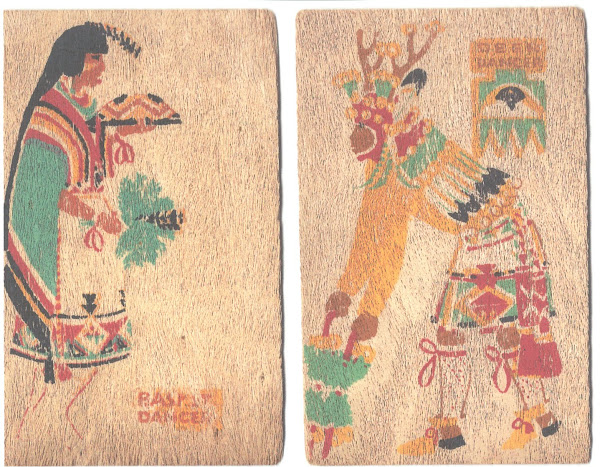

Joan wrote, “I want to clarify about the text and illustrations in

Children of Other Lands. The Hollings (Holling and Lucille) painted those full-page colored illustrations and drew all the marginal drawings. The plates for those were full-page illustrations originally used for the covers of

Junior Home Magazine. Holling had a short story to go with each of those covers that appeared on one of the first pages of the magazine.”

She continues, “During the Depression,

Junior Home Magazine went out of business. Platt and Munk bought those beautiful plates and used them in

Little Folks of Other Lands (1929) and

Children of Other Lands (1933). Holling's short stories were rewritten and made longer. Watty Piper was the writer. That was a pseudonym.” And, she added, “I have heard the pseudo writer could be one of a couple possibilities so I can't give you a definitive answer on that.”

A quick search of the Internet reveals “Watty Piper” was actually Arnold Munk, a Hungarian immigrant who co-counded Platt & Munk, the publishing house in Chicago, and served as in-house editor. He was best known for retelling the story of

The Little Engine That Could in 1930 and selling millions of copies. Platt & Munk today is a subsidiary of Penguin Books.

Now the story becomes interesting, but confusing:

Enter Eulalie (pron.

Ú-la-lee) Page. She was born Eulalie Banks on June 12, 1895, to Marie Minfied and Frederick Francis Banks, the youngest of nine children; in Southeast London, England. “All sources indicate that she had a real love and talent for illustrating from a very early age,” reported Kay Vandergrift of Rutgers University (

http://comminfo.rutgers.edu/professional-development/childlit/eulalie.html). At age 15, Eulalie “landed her first job as an illustrator for a children's page in a woman's magazine,” Vandergrift wrote. “At age 18, the book titled,

Bobby in Bubbleland, became her first published work. She was both author and illustrator.” (Ms. Vandergrift, professor emerita at Rutgers, died July 1, 2014.)

Platt & Munk commissioned her in 1925 to illustrate the book,

The Cock, The Mouse, and The Little Red Hen, edited by Watty Piper (presumably Arnold Munk). It was her first book published in the United states and the first of many published by Platt & Munk. In all, Eulalie illustrated some 53 mostly inexpensive children’s books, a good share published by Platt & Munk.

Among the works listed by Vandergrift under her résumé, however, is

Children of Other Lands, written by Watty Piper and published by Platt & Munk in 1933. This may be in error, however, because both Holling and his wife, Lucille, are listed as the illustrators of the book now in print and available on Amazon.

A follow-up conversation with Joan reveals the original book,

Little Folks of Other Lands (1929) published by Platt & Munk, became

Children of Other Lands (1933) with six fewer full-colored illustrations and lacking the Hemisphere maps on the front and back inside covers.

The original

Road in Story Land (1932) has a red & blue edition (arranged in different order). It became

Folk Tales Children Love (1934) and

Magic Story Tree (1964). The latter two books are the same except the stories are arranged in different order and have five fewer stories than the original Road in Story Land.

“So,” she writes, “one might think there are six different books while all the material comes from the two originals.” Confusing, or simply good marketing?